יין ושׁכר אל־תשׁת אתה ובניך אתך בבאכם אל־אהל מועד ולא תמתו חקת עולם לדרתיכם׃

ולהבדיל בין הקדשׁ ובין החל ובין הטמא ובין הטהור׃

Adonai said to Aharon, "Don't drink any wine or other intoxicating liquor, neither you nor your sons with you, when you enter the tent of meeting, so that you will not die. This is to be a permanent regulation through all your generations, so that you will distinguish between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the clean;

(Lev 10:8-10)

"AND AHARON WAS SILENT!"

A JOYFUL SERVICE.

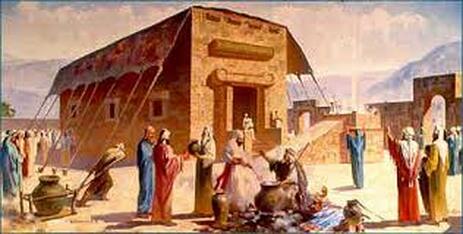

Our text this week relates to the death of Aaron’s two sons. It also brings to mind levitical laws concerning priests and defilement from the dead. According to Leviticus 21:1, a regular priest is not allowed to perform service in the temple if he has come near a dead body. As such, even if a close relative dies, he cannot tend to them if he has to perform Temple service that day. Though there hasn’t been a Temple for 2,000 years and Orthodox Judaism still try to live by these laws of purity concerning Kohanim, modern Judaism has decreed a law making exceptions in case of a relative.

On the other hand, there is no problem for a High-Priest to tend to the service of the Temple even when he has tended to the death of a close relative. Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda commented on this issue. He reminded us that the service of HaShem must be done in a spirit of joy so he says, “When a regular person [a regular priest] loses a relative, he is in a state of grief and therefore lacks the necessary joy. But the High-Priest had to be a person who reached the level that his service in the Temple would transcend any personal loss. When he performed the Almighty’s service, he was able to be in a joyous state regardless of what events had just occurred.”

Then Rabbi Naphtali makes a point about alcohol consumption. He says, “Because joy is necessary, one might mistakenly think that a priest could or even should take wine in order to put himself in a high mood. Therefore the Torah tells us that this joy must come from an awareness of the Almighty. It should not be artificially induced by means of a chemical substance that one ingests.”

In bringing in the subject of alcohol when talking of the death of relatives, Rabbi Naphtali follows the pattern of our parasha this week which starts with the death of Aaron’s two sons, and continues with the injunction concerning the consumption of alcohol,

"Don't drink any wine or other intoxicating liquor, neither you nor your sons with you, when you enter the tent of meeting, so that you will not die. This is to be a permanent regulation through all your generations, so that you will distinguish between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the clean;" (Lev 10:9-10)

WHY WAS AHARON SILENT?

Aaron performed his service though he had learned that his two sons died. It must have been difficult for him. Was he impervious to the death of his sons? Was he a detached parent? One could have expected him to at least say something, to make a statement such as Nachum Ish Gamzo who whenever something bad happened said,” גם זאת לטובה Gam zo letovah (This is also a good thing)”, or like with Rabbi Akiva, “All that the Almighty does is for good” but Aaron said nothing. He remained silent.

Aharon kept silent. (Lev 10:3)

It was not that he was untouched by the tragedy. The text does specify that in light of the situation, he took mourning steps (Lev 10:19). After the service was over, Aaron probably went and properly mourned the death of his two sons.

But here probably why Aharon remained silent after he learned of the death of his 2 son's. Rabbi Moshe Hacohen Rice teaches that when a person naturally walks in the path of joyful acceptance to God’s will no matter what, he does not have to keep convincing himself that everything HaShem does is for the good. That was the greatness of Aaron, he says, “He remained silent because he knew clearly that everything the Almighty does is purposeful.” He was indeed a high priest who reached the level that his service in the temple transcended any personal loss.

TRUE JOY FROM HASHEM'S SPIRIT.

It is told to priests that they cannot drink any kind of intoxicating drink during service in the tent of meeting which later became the Temple. It is not because drinking a little wine is sinful, (emphasis on “little” (Ecc 9:7; 1 Tim 5:23) as revelry and drunkenness are sinful as part of the works of the flesh (Prov 31:4-5; Gal 5:19-23.) Here again is what the text tells us,

"Don't drink any wine or other intoxicating liquor, neither you nor your sons with you, when you enter the tent of meeting, so that you will not die. This is to be a permanent regulation through all your generations, so that you will distinguish between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the clean; (Lev 10:9-10)

Intoxicating drinks have a tendency to dull our senses. This can therefore cause us to forget what has been decreed and not be able to distinguish between the holy and the common, and between the unclean and the clean, and therefore not teach the people properly which to be a sin into death: “so that you will not die.”

I’d like now to use all this talk about wine as a segway to a midrash that is found in the collection of midrashes on leviticus called Vayikra Rabbah. I will relate it as told by Rabbi Zelig Pliskin in his book, Growth Through Torah.

It is the story of a man who spent most of his money on his drinking. The children started to dread their future economic situation so they planned an intervention. One night that he was drunk, they tied their father up, brought him to a cemetery and left him there on the ground. They were hoping that when he would wake up from his drunkenness, their father would be so scared that he would never drink again. Little did they expect that that very night a wine carriage passed though the cemetery. The wine merchant was attacked and as he hurried the horses forward, a wine barrel fell off, rolled toward the drunk tied up man, and landed beside him with the faucet right next to his mouth. The man thanked Providence and kept drinking right there in the cemetery.

In a letter to his father, Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dresser commented on this story. He said, "We see from this that the Almighty leads a person in the way he wants to go. "

We may think that we are victims of our environment, of the influences that have surrounded us all our lives, but in a certain way, as the Rabbi says the Almighty leads a person in the way he wants to go.

This means that we are not where we are just because He brought us there. Sure He may have helped us to get there, but He helped us to go in the direction that we decided to go. Just like it was with Pharaoh. He was himself against the Children of Israel leaving, but after three plagues, we are told that it is HaShem who strengthened his resolve. Another way I heard it said was, WE are the sum total of OUR own decisions. This should make us think about our personal situations. We really have made these choices and good or bad, we have to live with them.

Rabbi Eliyahu didn't stay there in his letter to his father. He also concluded that, “If it is so with a person when he wants to do something that is improper, all the more so it is true when a person has a strong will to do what is good.” (Michtav mMeEliyahu, vol 3 pp 319-20)

Rabbi Paul concurs with the rabbi when he says,

To be zealous is good, provided always that the cause is good (Gal 4:18)

“MAY OUR JOY BE THE JOY OF HIS SPIRIT IN US.”

“MAY WE PRAY WITH JEREMIAH ‘TURN US AROUND’ …”

and then I will paraphrase from the famous Irish blessing, “AND MAY THE WIND BE AT OUR BACKS, PUSHING US ALL THE WAY TO YOU.”

(in Hebrew, wind and spirit are the same word)

RABBI GAVRIEL

RSS Feed

RSS Feed